One of the biggest questions on the left is unity in difference. How do you collaborate and struggle together when there are so many things keeping people apart? Two responses are popular now.

One is to examine differences carefully, work them out and work through them, and bring people together that way. Allyship, accomplice-ship, affinity groups, representation, and antioppression workshops/trainings are common on this path. This is very difficult, can be rewarding, but can also exacerbate divisions. It can also sometimes put too much emphasis on certain features of the struggle.

The other is to put the differences aside in favor of what people have in common. Socialists look to ‘class’ for this, or shared economic struggle in spite of ‘identity’ differences like race, gender, ability, sexuality. Focusing on ‘universal’ programs like Medicare for All and stronger unions is one way to do this, or a candidate like Bernie Sanders.

The unfortunate thing about these two responses is that both have to happen: people need to work through oppressive differences to unify in a common class struggle to make things better. Turns out those ‘identity’ issues are articulated with ‘class’ in our capitalist relations of production, and you can’t not address both aspects.

I’ve done a bit of thinking and organizing trying to advance this line, but I can’t report much success. I took a break from working on that problem given how bitter the project ended up.

But I bring it back up again because I’ve found an example that really confounds all the presumptions behind this dichotomy. I came upon it researching school funding and racial capitalism.

A Klansman joins the civil rights movement

I’m teaching a class on the history of school funding this semester, and in a great essay by Ester Cyna on a school district consolidation struggle in North Carolina, I came upon the story of Ann Atwater and C. P. Ellis.

Believe it or not, Ellis was the president of the Durham chapter of the KKK (an ‘Exalted Cyclops’ to be exact). Atwater was a local organizer, active with the civil rights movement in Durham.

There are some great resources on these two, their backgrounds, and their work together (including a movie!). Go and check them out. Suffice to say, they both grew up poor, each struggling under the US’s special brand of capitalism that promises sweet success but is bitter for most people.

The bitterness led Atwater and Ellis on different paths carved out by racial capitalism in 1970s North Carolina. Those paths led them to Durham’s City Council to advocate for opposite sides of a school district merger plan that federal courts mandated as part of desegregation.

Ellis was there on behalf of the Klan to oppose desegregation, Atwater advocated for it. Here were two people united by a class struggle that bitterly divided them. But a smart community organizer Bill Riddick broke through this divide and turned Ellis.

I think the turning of Ellis is a compelling thread to weave here, though it centers the white experience. Ellis did all the bad things. He was organized and violent until he got turned. But since white practices are one of the main obstacles to justice and socialism in the US, I think it’s instructive to focus on how this school organizing turned Ellis. How’d it happen?

Issue organizing

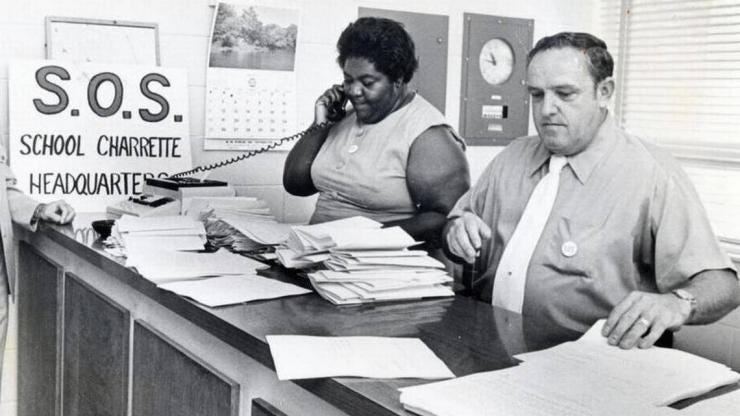

Riddick helped organize a ‘charrette’, which apparently is an intense community meeting focusing on a specific issue. He got Ellis and Atwater to agree to co-chair the event. During the course of organizing this event, Ellis says he had an epiphany that opened up the world, led him away from the Klan and towards civil rights and labor organizing.

Ellis says the initial collaboration was turbulent:

A Klansman and a militant black woman, co-chairmen of the school committee. it was impossible. How could I work with her? But after about two or three days, it was in our hands. We had to make it a success. This give me another sense of belongin’, a sense of pride. This helped this inferiority feelin’ I had. A man who ahs stood up publicly and said he despised black people, all of a sudden he was willin’ to work with ‘em. Here’s a chance for a low-income white man to be somethin’. In spite of all my hatred for blacks and Jews and liberals, I accepted the job. Her and I began to reluctantly work together. (Laughs.) She had as many problems workin’ with me as I had workin’ with her. One night, I called her: “Ann, you and I should have a lot of differences and we got ‘em now. But there’s somethin’ laid out here before us, and if it’s gonna be a success, you and I are gonna have to make it one. Can we lay aside some of those feelin’s?” She said: “I’m willing if you are.” I said: “Let’s do it.”

One of the main obstacles in desegregation is the perceived impact on property values among whites. Will market value decrease? Will ‘their’ district get worse? It’s a school funding issue because whites don’t want to pay taxes for education that BIPOC would benefit from. (There are also tons of good reasons for BIPOC not to want to integrate with whites.)

But this experience turned Ellis on these issues. Ellis describes the moment of connection actually happened when they shared experiences of their children getting made fun of in school:

We walked the streets of Durham, and we knocked on doors and invited people. Ann was goin’ into the black community. They just wasn’t respondin’ to us when we made these house calls. Some of ‘em were cussin’ us out. “You’re sellin’ us out, Ellis, get out of my door. I don’t want to talk to you.” Ann was getting’ the same response from blacks: “What are you doin’ messin’ with that Klansman?”

One day, Ann and I went back to the school and we sat down. We began to talk and just reflect. Ann said: “My daughter came home cryin’ every day. She said her teacher was makin’ fun of me in front of the other kids.” I said: “Boy, the same thing happened to my kid. White liberal teacher was makin’ fun of Tim Ellis’s father, the Klansman. In front of other peoples. He came home cryin’.” At this point – (he pauses, swallows hard, stifles a sob) – I begin to see, here we are, two people from far ends of the fence, havin’ identical problems, except hers bein’ black and me bein’ white. From that moment on, I tell ya, that gal and I worked together good. I begin to love the girl, really. (He weeps.)

As an education person, it’s striking that kids having a bad time in school because of their work that brought Ellis to Atwater.

So they kept at it. The meetings were difficult but Atwater and Ellis made it work. The charrette came up with a number of proposals around the integration, they brought them to the school board.

Ellis says he disagreed with some of them, but was so committed to the project and the people that he advocated for them anyway. “I thought they were good answers. Some of ‘em I didn’t agree with, but I been in this thing from the beginning, and whatever comes of it, I’m gonna support it.” To me, this is striking because at this point Ellis is supporting things he doesn’t support. He isn’t on board with the integration but he’s on board with it. And what got him there? The connection and work with Atwater.

The way he describes his turn is pretty compelling:

The whole world was openin’ up, and I was learnin’ new truths that I had never learned before. I was beginnin’ to look at a black person, shake hands with him, and see him as a human bein’. I hadn’t got rid of all this stuff. I’ve still got a little bit of it. But somethin’ was happenin’ to me. It was almost like bein’ born again. It was a new life. I didn’t have these sleepless nights I used to have when I was active in the Klan and slippin’ around at night. I could sleep at night and feel good about it. I’d rather live now than at any other time in history. It’s a challenge.

Now some socialists out there might think this is ‘race reductive’, that it was all about Ellis working through his oppressive consciousness. But Ellis went on to become a labor organizer and work at the class struggle.

He went back to school, got his GED, and all the while worked as a repair man at Duke University. As he studied, he said he had a general sense that “things weren’t right in this country” and wanted to tell the story of his work in Durham.

I come to work one mornin’ and some guy says: “We need a union.” At this time I wasn’t pro-union. My daddy was anti-labor too. We’re not gettin' paid much, we’re havin’ to work seven days in a row. We’re all starvin’ to death. The next day, I meet the international representative of the Operating Engineers. He give me authorization cards. “Get these cards out and we’ll have an election.” There was eighty-eight for the union and seventeen no’s. I was elected chief steward for the union.

The way Ellis then talks about his experience organizing sees his turn towards unity in difference complete. His understanding is completely shifted.

When I began to organize, I began to see far deeper. I began to see people again bein’ used. Blacks against whites. I say this without any hesitancy: management is vicious. There’s two things they want to keep: all the money and all the say-so. They don’t want these poor workin’ folks to have none of that. I begin to see management fightin’ me with everything they had. Hire antiunion law firms, badmouth unions. The people were makin’ a dollar ninety-five an hour, barely able to get through weekends. I worked as a business rep and was seein’ all this.

Stuart Hall would call this an example of unity-in-difference. Ellis knows the deep divides between Blacks and whites better than anyone. He himself was a violent white supremacist. But after his experiences with the charrette and education organizing, he opened up. Saw far deeper. And got into labor organizing.

How’d Ellis get to this labor struggle? Through an issue campaign, specifically around school district consolidation. He worked out some of the most trenchant, cellular practices of racial capitalism around property to get active in class struggle.

Putting in situations of direct struggle

The lessons here are many. One that comes to mind is something one of my organizing heroes Myles Horton says in his autobiography: you have to put people in situations where they confront the structures you want to change. That’s what Riddick did with Ellis.

I’m also thinking of something that my other organizing hero, Barbara Madeloni, told me once. The reason we organize is to put people in direct contact with the class struggle. You have to bring people to the forces you want to change.

If the question is how to create unity-in-difference, and Ellis is an example, then the example shows how to work through oppressive differences you have to put people in the situation of the class struggle. You can’t set aside the differences in favor of some simpler ‘universal’. But you also can’t focus on the differences exclusively. In this case, the struggle was school desegregation and consolidation. Riddick put Ellis in direct contact with that struggle.

Like Stuart Hall says too, race is a modality through which class is lived. I think this theoretical conclusion is difficult to operationalize, but the Ellis case provides one example. We have to see situations where we can put people in direct contact with the struggle by bringing them to the forces we want to change.