Whenever someone asks me what we should do about school funding inequality, I mention tax-base sharing, the regional system set up in the Twin Cities in 1971 and then in the north of Minnesota in 1995.

This system is pretty cool. It’s not perfect but it’s the kind of thing we should look at when thinking about how to reduce inequalities between local governments with radically different property values.

Here’s a quick post on what tax-base sharing is and how it works.

Sharing growth

Minnesota passed the Fiscal Disparities Act in 1971. Property values between municipalities were very unequal and progressives wanted to change it so poorer counties could get much needed revenue for their people. Conservatives called it “prairie socialism,” but it passed.

As the metropolitan council’s website explains, tax-base sharing is all about sharing growth. Each county contributes 40% of their growth in property taxes to a regional pool.

Money from that pool gets distributed back to the contributing governments based on their populations and market values of property relative to the average value for the whole area.

Everyone puts in a certain amount based on their growth and everyone gets something back based on their population and property value.

Putting in, getting back

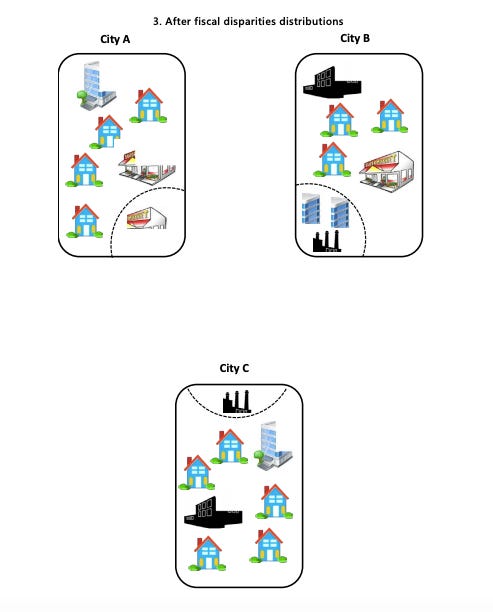

A report on the program from February of last year includes a series of helpful pictures to show how this works.

Let’s say you have three cities: A, B, and C. Each of them have different properties they can tax like homes, factories, offices, and restaurants. Each city brings in different amounts of revenue for each property. C has the most, B has the least, and A is in the middle.

The tax-base sharing program creates an areawide pool. Each city contributes a percentage of the growth in their tax base to the pool, which is basically a percentage of the money they made by taxing their properties.

In the picture above, you can see little pieces of the offices, restaurants, and factories go from the city into the pool.

Then each city gets a distribution of the money in the pool based on their population and property values.

So everyone puts in and everyone gets something back.

The graph below shows the contributions and distributions between eight counties in the Twin Cities metro region for 2018. Hennepin contributed 52% of its net tax capacity and got back 36% of it, making it the only county to give more than it got back. Every other smaller county put in less and got back more.

The tax pool has steadily increased over time, reducing the inequality between counties in the region. According to the council’s website

tax-base sharing narrows the gap between communities with the highest and the lowest commercial, industrial, and public utility property tax base per person. For communities with over 10,000 people, the difference is 4 to 1 with tax-base sharing and 11 to 1 without it.

I think this model could be really helpful for thinking about the nuts and bolts of creating regional equity among local governments with drastically different property values. Again, it’s not perfect. But without revolutionary conditions in property relations, this is one of the better systems I’ve seen in the US context.